Heartbreak you can dance to

Flaco el Jandro's world of Romanticumbia

Y La Bamba came to my hometown for a Monday night show. I bought tickets as a casual fan– I like a few songs off their new record Lucha– and hoping to sink deeper into their world by seeing them live. I know some people only see shows when they can sing every word with their idols, chasing that peak emotional experience, but some of my most rewarding nights have come from walking in with zero expectations—not knowing what to expect. I like being pleasantly surprised.

I also make a point of catching the opening act whenever possible. I’ve fallen in love with more artists this way than I can count. Opening acts are usually hungry, eager to connect, performing for crowds that haven’t arrived yet or aren’t paying attention. And crucially: they’re typically handpicked by the headliner. That’s a stamp of approval worth respecting. It sounds obvious, but plenty of people skip openers and miss out.

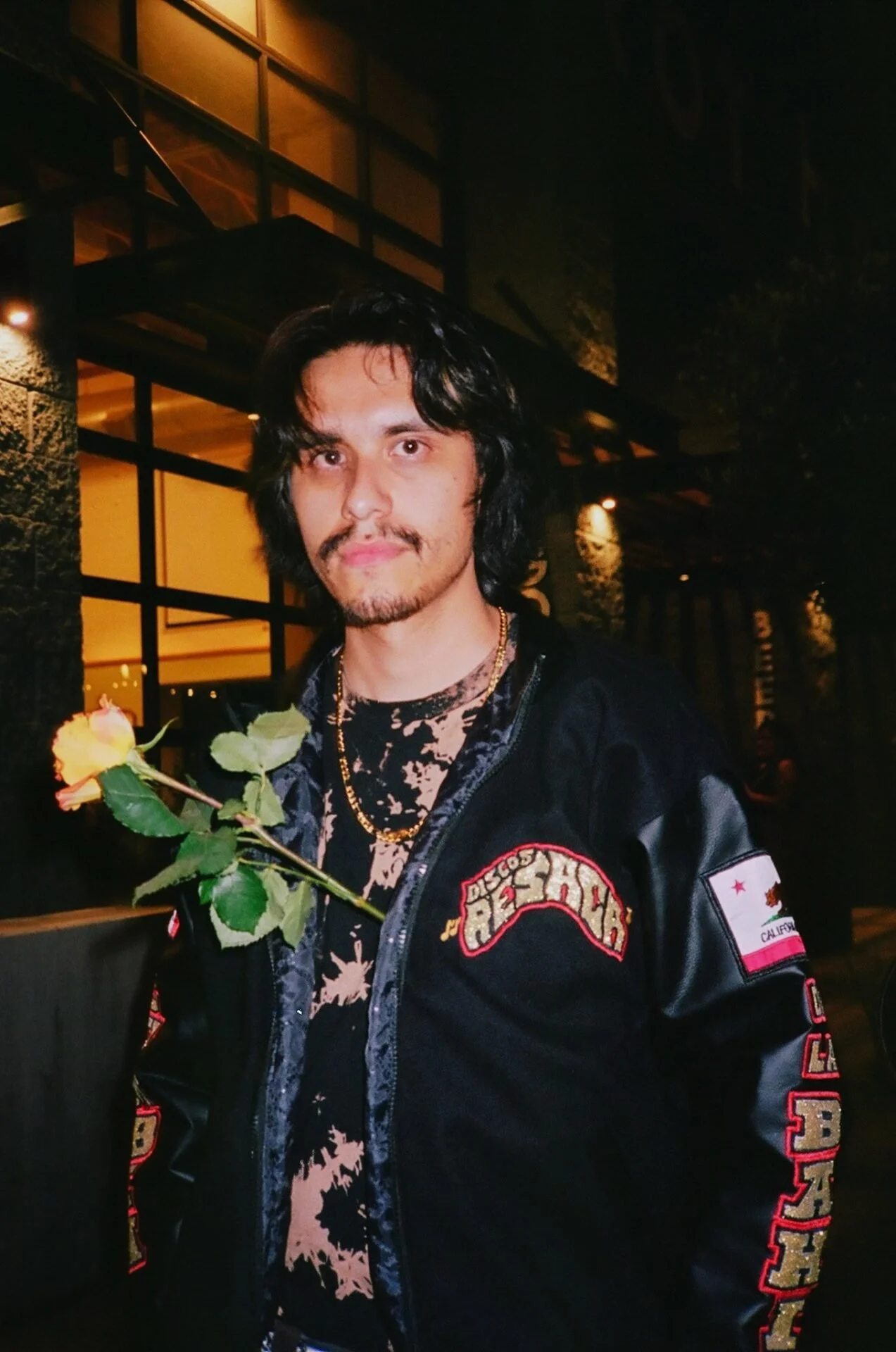

Which brings me to the incredible night I spent dancing my ass off to Flaco El Jandro—the project of Salinas-born and raised musician Alejandro Gomez. His set was alive with rambunctious Latin rhythms and styles, threaded through with an unmistakable indie pop sensibility.

Nicknamed Flaco, he learned guitar as a kid and played in bands throughout his teens before launching Flaco El Jandro at 21 with his first EP, Canciones para curar la depresión. In 2023, the band performed at the San Francisco stop of the NPR Tiny Desk Contest Tour, leading to showcases across the nationwide NPR network. In 2025, he released his third EP, Salaztlan, and has been touring the US and abroad.

After the show, I discovered we’re both Otters1—graduates of Cal State Monterey Bay. We made plans to talk more. What follows is a cleaned-up version of our rambling conversation about music, consciousness, and what it means to make Chicano music right now.

I saw you open the Y La Bamba show in Sebastopol and I loved dancing to your music. You have a thing with rhythm going on. What do you understand about rhythm and movement?

I feel a concert experience in general should be very interactive because it’s nice to go to a concert where you’re watching a band you’re excited about—you’re watching and listening—but it’s a lot more exciting if you can participate. The music, whether it’s Cumbia or anything where the audience is interacting in some way, there’s a specific dance or specific movement, the back and forth happening between the audience and the performers just makes it a more memorable, special experience for everybody. When that line is blurred between the audience and the performers, it makes it exciting. You feed off of that when you’re performing. It’s a much different performance for you to play a crowd that’s watching as opposed to a crowd that’s dancing.

I’m curious as a songwriter, how you birth rhythm in such a way that comes through so compellingly in your band? How do you think about rhythm from that point of view, rather than the performance point of view?

That’s actually something that I feel I struggle with, because I write by myself mostly. And it’s really easy to do just sad songwriter stuff. Depressing. I try to keep that in mind, try to think ahead as much as I can: what’s gonna be something where I can be heartfelt and express something that I’m trying to say, but also make people dance and make it so that this song is a fun experience and not just fully depressing.

I write everything on my own, for the most part. Sometimes I’ll write stuff and bring it to the band, but I pull up a lot of loops, whether it’s drum machines or samples or whatever, and play along to that. So it always has this heavy movement to it.

I’m inspired a lot by people who did stuff where it was very—they didn’t take themselves too seriously—but they could also write things that really made you think. Clever lines and lyrics that would get in your head, but it was always moving. There was always song or music that you could dance to.

Photo: Emily Atkinson

Your song No Te Pido was inspired by a Frida Kahlo poem. The song is very danceable, but the lyrics are very naked and stark about being in the position most people have felt, “I know that you just don’t love me the way I love you.” You’re kind of desperate, but then you’re getting people to dance about that.

That style specifically—it’s also really interesting to me because that’s rhythm making. It has a thing that you could move to, but it’s also really sad. All the songs are always heartbreaking songs. Tear-jerkers.

I think that’s an inherent thing in Latin music in general. And that all goes back to the African roots of all Black music. It’s rooted in rhythm. And Bolero specifically is a style of music originating in Cuba. It made its way into Mexico. And that’s the style, that’s why it’s kind of pairs that way. But yeah, in general my music’s heartfelt, but you can dance to it.

When you’re writing a song, you’re obviously a skilled lyricist, but you’re also paying attention to the music. Do you feel like you’re interested in more music or lyrics – one or the other? Because a lot of people feel like one matters more.

That’s a good question. I think right now where I’m at in my life, I don’t put enough practice into writing songs or writing lyrics. So I do consider myself more of a musician than a lyricist.

I spend way more time putting together music and compositions and arrangements instead of writing lyrics. And that’s where the clash kind of happens. If I’m solely focused on writing a good story, then it’s harder to maintain the idea of “this has to be dancing” and “how’s this gonna perform live?” and “how are the chords going to work?”

But yeah, I mean, it’s a practice. I think people forget that it’s a practice, just like playing guitar is a practice. Like drums, whatever style of music or instrument, you have to practice it in order to get better, in order to maintain it. Songwriting is the same thing. You have to practice songwriting and always be writing and always be working in order to get better, in order to have a process.

Do you feel like you write more autobiographical songs? Or is Flaco el Jandro a hologram of you? Or are you writing about characters?

I try to just relate it back to the human experience because we’re never gonna get away from the human experience and something that people can connect to. The only human experience that I’ve experienced is my own, so everything goes back to things that I’ve experienced. Sometimes it’s something specific or sometimes it’s broader things, and then sometimes I tell stories about other people, things, ideas or concepts.

Photo: Jonathan Ordiano Hewitt

We share an alma mater — you studied Chicano music at CSU Monterey Bay, right?

I studied music. I got my BA in music engineering and I did my capstone on the history of Chicano music.

I wanted to go back to school to learn music theory so that I could pass it on to my students and feel like more of a legitimate music teacher instead of just a guitar teacher showing chords. I wanted to give all my students a foundation that they could work off of — the kids in my area aren’t really given as much. {Ed. note: Alejando teaches music at two local non-profits – Alisal Center for Fine Arts in his hometown of Salinas, and Palenke Arts in nearby Seaside.} That’s why I went back.

My last EP, Salaztlan, was supposed to be part of my capstone basically. That took about two years. There’s a lot of really cool collaborations on there. Gabi Bravo is amazing. And Pak Joko is singer-songwriter from Indonesia via Haiti. He doesn’t speak Spanish, but his whole album is in Spanish and he wrote it and I kind of just helped him with it, produced it.